Sentient Design: AI and Radically Adaptive Interfaces

Sentient Design is the already-here future of intelligent interfaces—AI-mediated experiences that feel almost self-aware in their response to user needs. Instead of treating AI as a tool, Sentient Design invites you to use AI as a design material: What does it mean to weave intelligence into an interface? Static presentation gives way to radically adaptive user experiences conceived in real time. This lively session gives you the framework and examples to create intelligent interfaces in your own practice—right now, today—building remarkable experiences with AI while contending with its risks.

Here is the complete transcript:

Josh

We’re here to talk about the new kinds of experience design that we’re able to do with AI and machine learning. Sentient Design is what we call the form, framework, and philosophy of designing intelligent interfaces. We’re going to get into that in just a minute, but first some introductions.

I’m Josh Clark. I’ve been doing UX design and product design for the last 30 years. I’ve led design agency Big Medium for 25, and I’ve written a lot of books about UX and product design for O’Reilly, for A Book Apart, for Rosenfeld Media. So I’ve always thought I’ve got a handle on this UX and product design stuff—the best practices. I’ve got some confidence. This has been my career.

But as I’ve been working with AI and machine intelligence for the last several years, I’ve realized that a lot of these hard-won assumptions need to be revisited, and that’s where this one comes in.

Veronika

Thank you. Hi, everyone. My name is Veronika Kindred. I’m a designer and researcher with Josh at Big Medium. I’m an elder Gen Z, so my whole life has been mobile and internet native, you know, static web interfaces have always been a part of my life as they are now a part of all of our lives. The algorithmic TikTok-like experience is native to me.

But also my career is AI native. I started at Big Medium about six or seven months after ChatGPT hit us all and changed our experience of the world as we know it. So my whole time at Big Medium, I’ve been exploring this explosion of AI and my professional work has really focused on the design applications in this interface.

Josh

So Veronika doesn’t have as much experience as I do—but also she’s not burdened by as much experience as I am. So what you’re looking at here is two generations of designers—and literally two generations. Veronika is not only my colleague; she’s also my daughter. I’m very proud of you, sweetheart. And so very happy to be up here with you.

But this is also a really productive work collaboration. This is a moment where old heads like mine need some new perspective—and need to have folks like Veronika who ask questions like, “Wait, why are we doing that? Does that still apply?”

AI is weird. It’s a really strange design material. It lets us do things that we couldn’t do before, but also introduces new problems that we haven’t had before. So we do need new perspective and takes on this stuff.

So at last, what does it mean for us to have new kinds of user experience and product design with AI? How does this change things? That’s what we’re here to talk about today, and we’re going to talk about that in five chapters. So Veronika, to you.

What the hell?

Veronika

All right, everybody. Chapter one. Are you ready? What the hell? Guys, what’s going on? What’s up with AI? How do we use it? What are we supposed to do with it? What do we make of it? What does it all mean? What are we doing here?

We’re getting so many conflicting messages about to use it, about how to use it. In fact, each of us are getting conflicting messages about it every week, every day, every hour. It sounds, it feels like it’s wildly confusing.

Josh

One moment I’ll say, “It’s so smart! I can’t believe it can mimic any image style. It’s coding apps for me on the fly.”

Veronika

And then the next we’re asking questions like, “Why can’t it count the number of R’s in the word raspberry?” Or, “Why is it telling me to put glue on my pizza?”

Josh

BUT IT’S SO BIG! It’s going to change everything! AGI—artificial general intelligence—it’s right around the corner!

Veronika

We hear all these big promises, but realistically, I’m using it to write emails and LinkedIn posts.

Josh

It’s going to change everything! It’s going to revolutionize science!

Veronika

Sure, or it will ruin everything. It’s going to ruin humanity as we know it, and it will write all of our poetry while we’re relegated to washing the dishes.

Josh

So as we tried to figure out what to do about this, we turned to the greatest philosopher of our time.

Snoop Dogg

It’s blowing my mind because I watch movies on this as a kid years ago when I used to see this shit, and I’m like, “What is going on?” Then I heard the dude, the old dude that created AI, saying, “This is not safe because the AI’s got their own minds. And these motherfuckers are going to start doing their own shit.”

I’m like, “Is we in a f**king movie right now or what?” The f**k, man? So do I need to invest in AI so I can have one with me? Like, do y’all know? Sh*t, what the f**k?

Veronika

Even Snoop doesn’t know. Even Snoop! So what are we supposed to do here?

Technology gives, technology takes

Josh

It doesn’t help that we live in a very polarized society, right? That this definitely touches the conversation about AI as well, where everything is either amazing, the biggest thing since fire, or it’s terrible and it’s useless. With AI, as in most things, the truth is probably somewhere in the middle, in this sort of hazy, fluid, gray space of both good and bad. But when you look at all the good, I mean, sincerely look at all this stuff, these sort of superpowers that we have now as designers and developers with AI, it really is truly breathtaking.

Veronika

Right, and then you look at all of the risks, all of the risks, all of the mitigations, and these are in no particular order here. And they’re very real. They’re a really big deal.

I want to harp on this point for a moment because we truly believe that large language models are the purest distillation of extractive capitalism to date. And that’s not a small deal at all. They have sucked up all of the world’s content without any credit to the creators. And it requires punishingly vast amounts of energy to use.

And these are not small things. This will have knock-on societal and economic effects for generations, issues that we haven’t even begun to think about or consider yet.

So as we move through all of these things, like make no mistake, this is fraught, and we’re telling you how to use it. We’re telling you how we think it should get done. But it’s not a slam-dunk positive for society.

But that’s not new either. Technology gives, technology takes, and it really is a back-and-forth.

Josh

I mean, ultimately, it’s like, how do we use this stuff? So, you know, I think that it makes a lot of sense for some of you are probably skeptical, maybe fearful, uncertain about AI. That is so logical, just based on that last slide that we were looking at. But there’s also so much opportunity. How shall we use AI and put this to use in our work?

Many of the problems in that last slide are not inherent to the technology. It doesn’t have to be an energy suck. Look at DeepSeek. It doesn’t have to be expensive. Business models don’t have to exploit content creators.

But do no harm is also sort of a low bar, right? So like what we’re going to explore today in the context of all those very real concerns is what can we do in our sphere as product designers, interaction designers, user experience designers, what can we do to create dramatically new, better, and more valuable experiences?

I don’t think that as an industry, we’re yet doing that. I think that we’re still doing something at a different level. At Big Medium, we talk to a lot of digital leaders over time. And Veronika, you do a ton of research around this stuff. What are you seeing in how people are approaching AI and digital organizations?

“Efficiency” misses the opportunity

Veronika

Unsurprisingly, the obsession right now is with efficiency. And I apologize. This slide in the past week or two has really taken on a very DOGE-ish tone. So sorry about that.

But there’s a preoccupation with efficiency, efficiency, more efficiency. How can we get higher ROI? How can we drive down costs? The same focus that you might expect from corporations. And we’ve especially seen these efficiency efforts focused on things like software development, marketing in the form of image generation, and human resources.

All of these are very tool-focused applications, and how AI can change processes and workflows. The same has been true for designers as well—how does AI affect our idea ideation process in the initial stages?

Josh

So we’re focusing on process—how we make, and not what we make.

Veronika

Correct. Yeah.

Josh

So that feels like a missed opportunity.

Veronika

Right. Even to the degree that designers are using building AI into their workflow, it is very tool-focused and very transactional. We’re seeing features bolted on that are generating text or editing images—you’re throwing in a text field to edit content, those types of things. It is a very engineering-forward perspective of AI. The focus is on changing process , not on the resulting experience.

What kind of experiences can we enable?

Josh

I love that point that it’s an engineering-focused thing—and that’s a natural moment for new technologies like this. We ask what does it do instead of exploring it more experientially: how do we level that up? So a lot of the stuff we’re seeing right now is very transactional experience design, as Veronika mentioned.

But friends, there is so much untapped design opportunity right now! And that’s what we’re going to spend the rest of the time talking about today. We want to share some ideas about how designers can think about AI. Not just what we can make with it, the generative AI part, but what kinds of experiences can we enable?

So I mentioned before we’re going to do this in five parts, five chapters to this talk. We’ve already done a little bit about “what the hell.”

We’re gonna go talk about this as a new design material—how do we think about this, not as a tool, but as something that you can weave into interfaces to make an intelligent experience.

Those kinds of things are radically adaptive experiences. Things that can really sort of be extremely fluid based on user need and intent.

And then the role that we have will change as we start to allow some of these experiences to be mediated by AI and for the user and AI to work together directly. Where does that leave us? We’ll talk about that.

And then finally some new ways to think about generative AI in that last chapter.

A new design material

So let’s get after it. Let’s talk about this new design material. Instead of thinking about AI as a tool, we want to challenge you to think of it as a design material. What does great design look like when you weave intelligence into the very sort of fabric of the interface?

And speaking of great design, this is a sketch I made of a little interface. I drew it in an app called tldraw. It’s a platform for building whiteboard applications, things like Miro or FigJam. And tldraw added a feature called Make Real. It’s a feature that turns your sketches into working code.

So I select what I drew here and I click Make Real, and then after a few seconds, it actually builds the interface. This is more than just drawing it or building the UI widgets. When I click in here and start interacting with it, it actually works! It inferred from my sketch what the thing should do and how it should behave. I’ve just sketched a little miniature application here to actually do its thing.

Let’s look at another one. So here we have a sketch of a notebook on the left. The sketch has some instructions to make a page flippable notebook. And so Make Real has generated this prototype on the right. Let’s try it. It works! Very pretty.

All right, one more of these. Draw a keyboard here on the left with a few instructions, and Make Real creates a working keyboard on the right. It even adds sound! All right. That’s pretty cute.

Kind of mind-bending, but it’s actually an example of one of the many functional design patterns that we’ve identified in Sentient Design. Veronika?

Veronika

I absolutely lost my mind when it added sound. I thought that was so cool. But Josh is right. We call this pattern the Pinocchio design pattern. You’re turning the puppet into a real boy, get it?

You’re taking a sketch and you’re turning it into a working prototype. You’re taking a prompt and turning it into a full essay. You could take the opening riff of a song and turn it into the whole thing. Basically, you’re taking an idea and a concept and you’re turning it into a working reality. And this is really machine intelligence acting as a collaborator, turning low fidelity into high fidelity.

So we have an example here. This is a Figma plugin we made at our agency, Big Medium. So on the left here, there’s this wireframe that I drew and we’re going to run the plugin. We’re going to click and—ta-da—there’s a layout created by the plugin that uses the design components from our client’s design system.

So, you’re able to select and launch and bam! It’s not a finished design by any means—I think we can all agree on that. But it takes a wireframe, gathers the components, and sets the table for the designer to finish the meal. And it all happens in the context of your working environment, which is the part here that I really like.

Here, it’s happening in Figma and staying in the environment. You’re maintaining the context and allowing for the most cohesive experience possible. There’s not a separate mode, like a chat experience off to the side. You’re continuing to work in context.

Josh

So a similar example of that, coming back to my little sketch in tldraw, the whiteboard app. I’ve decided to add my edits by putting this text in arrows and marking it up, you know, like I would in a whiteboard.

When I select it all and then click make real, it generates another version based on my notes. And you can see here, oh, roundedness has been changed to roundness. And the scale under the hood for size has changed from 20 at the left to 200 on the right. And it’s a red triangle.

So it’s a subtle but important interaction decision, which is: we’re not going to create new modes for this. We’re going to think about how to put intelligence into the interface itself so that you can continue to use the same interaction mode. You just sketch away, mark it up, keep going.

The intelligent canvas

Josh

I want to be clear about some of these examples because what we’re doing here is generating some code under the hood and code generating some design. That’s not the point of these. In fact, I feel really strongly, I know Veronika, you do too, that the component assembly or code generation that we’re seeing here is not doing the real work of designers or developers.

So much of design is embedded in that original wireframe that Veronika had sketched in that earlier example. Not the high fidelity object. Great design is in the what and the why and the sense-making. So what kind of new “what and why” does machine intelligence unlock?

This is what Sentient Design is about: What happens when you weave intelligence into digital interfaces? Instead of thinking of AI as a tool, think of it as a material, as I said.

What happens when you weave intelligence into digital interfaces?

The handful of examples we’ve seen so far allows us to reimagine the interaction surface as an intelligent canvas. When you weave that Pinocchio pattern or any machine intelligence into the fabric of an application, its interface becomes a radically adaptive experience, radically adaptive surface, right?

It can become something new. It can change its behavior, its content, its structure, sometimes all three at once. And that’s a far cry from our traditional static interfaces. It’s also so much more than chat, which is what we tend to think of as an intelligent interface at the moment, right?

Now this is only one direction, this idea of intelligent canvas for imagining new machine-intelligent experiences. We’ll talk about more, but the intelligent canvas is a powerful example. And like the Pinocchio pattern, this experience pattern of intelligent canvas is one of many in Sentient Design. Again, we’ll explore a few more of those. But let me just show you some mainstream consumer examples of this intelligent canvas idea.

The iPad calculator app that came out last fall has a feature called Math Notes that lets you draw equations and make them interactive. So here at the bottom left, if I turn that into an equation by making y equals, now I can add a chart to this. Great, that’s charting what that is. Those scribbles up at the top though, those are actually variables. So if I tap the 30, I can change that and you can see the graph is changing.

You can just draw this interface to make it do what you want to do—and it works. The point of all this is that you’re making the application canvas itself intelligent. It’s like telling it what kind of application that you want it to be as you do it.

This is just spreadsheet functionality, right? But we’ve gotten rid of the grid and let the user draw whatever they want including images on it. So this is something that is like on-demand software or at least on-demand interface.

Draw an app to adjust recipe portions or to calculate your calorie usage in your workout. Just draw what you need. Maybe it’s disposable software then, right? Wait, I need this. Just draw it and go.

These are examples where the system adapts to you instead of the reverse. It’s interaction on human terms instead of machine terms. We have interfaces now that can discern context and intent and just do the right thing. Sometimes explicitly like the iPad example, sometimes implicitly where it’s just discerning what you want to do.

On-demand interfaces and disposable software

This begins to approach on-demand applications. Claude is pretty amazing at this. I’m sure some of you have played with this. In chat, you can tell it to make an app and start using it and improving it right away. So here I told it to build an asteroids game that I could play in the browser and in seconds I was playing it during the chat and then asking it to make changes. So I told it to add scoring and sound effects and then I typed in add zombies. I didn’t even know what that would do. I had nothing in mind, but it added these green asteroids that started chasing me around. It created this on-demand thing that didn’t exist a few minutes ago and was just now tailored to me.

Veronika

I also love Claude—and while Josh is going around playing his little Gen X games. I’m going to do some work. So I asked Claude to check the accessibility contrast between two colors. And on its own, it decided to write out this whole application for the task. I didn’t ask for it, but because that’s what it needed to complete the task, that’s what it built.

So it’s on-demand in the moment and then entirely disposable. It didn’t even use it in the final answer.

Josh

Pretty crazy.

From searching to manifesting

Veronika

We’re used to this discovery through search process when we’re looking for answers. We’re using search like Google or we’re using curation like a social media, but I mean, oh my god look at what’s happening, right?

You’re able to totally manifest the experience you want. And this is really new to interaction design and it’s crazy and it’s exciting and full of opportunity.

But I want to be careful when we say manifest because manifest can sound a little bit like we’re saying making. But today we’re talking about more than just like what machine intelligence can make.

Josh

Right. So the point of these last few minutes is this: machine intelligence is our new design material.

Machine intelligence is our new design material.

All of these examples weave intelligence into the canvas of the interface itself. So the interface becomes not just responsive but radically adaptable. It can manifest as something new as Veronika was saying. So just like HTML and CSS are design materials or dense prose or data is a design material. It wants to be used in a certain way.

So as we think about and explore what we can do as designers with AI and machine intelligence, we want to find out not only what it can do but what how it wants to be used and how it doesn’t want to be used.

The attributes of Sentient Design

Veronika

Right, the grain of the material. This all adds up to something called Sentient Design which really describes the form of this new experience. It’s the form but it’s also the framework and philosophy for working with intelligence as a design material and as our interfaces become more aware, designers must also be mindful of the opportunities and risks and that’s what Sentient Design is.

Josh

And if I can actually just interrupt… Friends, we have a book coming out later this year from Rosenfeld Media, and it’s going to be about all these things.

We’ve got postcards here with some information about the book. Feel free to come up and grab one of those later including some information that you can get to keep up to date with Sentient Design while you’re waiting for it to arrive at your favorite bookseller. Sorry to interrupt.

Veronika

No, all good. So Sentient Design, we’re talking about intelligent interfaces that are aware of their context and intent. They’re radically adaptive to user needs. They’re collaborative. They’re multimodal. They can go from text to speech to images. They’re continuous and ambient. They’re there when you need them. They’re gone when you don’t. They’re deferential. They’re there to suggest rather than impose.

What’s not included in this list, not explicitly, is making stuff. Because while making images or generating text can be a mean or a form of Sentient Design, that’s really not what it’s about.

Radically adaptive experiences

Josh

This brings us to our third of five chapters in this talk, which is radically adaptive experiences. This is one of the characteristics that Veronika just mentioned, and it’s core to what we’re talking about here.

Chatbots of large language models are an example of this, right? You can ask them anything, totally open-ended, and it will respond. You can follow a completely meandering, one-of-a-kind experience that is radically adaptive to you. It could not have been anticipated by any designer in terms of the content path that it’s following.

What Sentient Design asks is: what happens if we take that same open-endedness, that same radical adaptability, and bring it to any interface? These are interfaces that are conceived and compiled in real time based on the context and intent of the user.

What happens if we bring open-endedness to any interface?

What does this look like? And also: how do we avoid turning this thing into some kind of crazy robot fever dream? How do we put some guardrails around this so it has some coherent shape?

Here’s an example from the Google Gemini team. Gemini, of course, Google’s AI chat experience. And while this demo starts in traditional chat, it does something exciting. We call this experience pattern bespoke UI.

Let’s say I’m looking for inspirations for a birthday party theme for my daughter. Gemini says, “I can help you with that. Could you tell me what she’s interested in?” So I say, “Sure, she loves animals and we’re thinking about doing something outdoors.” At this point, instead of responding in text, Gemini goes and creates a bespoke interface to help me explore ideas.

Josh

It actually changed the interaction mode from a text chat to a GUI—with an interface pattern suited to the specific context proposed in the chat.

If we look under the hood at what’s going on here, this is the structured data that’s passing from the system to the UI layer. What we can see here is that it’s saying that there’s some ambiguity, that we don’t know what kind of animals the daughter likes, and we don’t know what kind of party that they want to have.

But we’ve got enough information to ask. And so it’s like, “All right, well, let’s proceed then.” And then it identifies the content to explore: the party themes and activities and food options.

But this part is really interesting. Here in this layout, we see this data type listDetailLayout. This is a design component to use—this is using a design system!

So this has got this little constrained design system with some rules around context for when to use each. So it’s got some structure. We do this with humans with design systems, too. Here’s the scope of things to use for specific solutions for specific problems.

Let’s see how this story continues.

Farm animals. She would like that. Clicking on the interface regenerates the data to be rendered by the coded route. Ooh, I know she likes cupcakes. I can now click on anything in the interface and ask it for more information. I could say, “Step-by-step instructions on how to bake this.” And it starts to generate a new UI. This time, it designs a UI best suited for giving me step-by-step instructions.

Josh

That thing that he did with the word “cupcake”; you can interact with any element in the interface and zoom into a new direction. That is a path that couldn’t specifically be designed for. It has this complete open-endedness and then the system follows and creates a new UI based on what you select and what you ask for.

It’s not a path that you can design for specifically, but it’s enabled by making machine intelligence the mediator of this.

Veronika

In other words, we can use machine intelligence for experience, not only functionality.

We’re able to use LLMs to understand intent. We can collect and synthesize information. We can select the right UI and then we can deliver it.

You can take this out of the chat experience for a moment and really ask yourself, what does this mean for data dashboards? How could we populate a specific area or corner of the interfaces with just-in-time experiences suited to the specific need of the moment?

This is an example from Salesforce generative canvas. It’s a plugin for Salesforce that assembles dashboards and content based on context. So here we’re using the user’s calendar for context to prompt the content of the dashboard. It’s using familiar design patterns from the Salesforce design system. It’s pulling from the usual Salesforce data sources. It’s just assembling them on the fly.

So design system best practices become really more important than ever. We’re giving the intelligent interface the design system to use for its own expression.

Josh

So we can we can embed intelligence into traditional GUI interfaces and have them make some decisions for us. That’s what those previous two examples were about.

Let’s get a little bit weirder with another example. This is a little exploration that we created called Sentient Scenes.

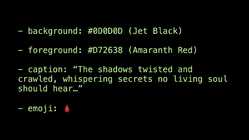

You give it a scene like “the submarine descends,” and then it acts it out. The little square starts to be the hero in this scene. You can give it another prompt like “HAL 9000” from 2001 a Space Odyssey, and it’s gonna act that out too. It changes its form.

This is a radically adaptive interface. It changes style, mood, and behavior based on user intent. There’s even a kind of personality that’s implicit in the square’s motion and the way that it acts out the scene.

If we want to see, you know, what happens when “a wizard’s spell goes terribly wrong,” we get this frantic vibe, and it’s got these wizardy colors—fun!

We’ll look at how this works in just a second, but first: this is just a little toy, but some of the implications are quite big.

It explores some provocative themes here of intelligent interfaces beyond chat. Instead of talking about this scene, the interface becomes the scene. It’s got some personality and presence without pretending to be human. It’s got this awareness of context and intent beyond just the description. It’s getting the mood and sensibility that’s implicit in what I’m asking for in describing these scenes.

It has the open-endedness that is part of radically adaptive experiences, but within constraints. All of the scenes feel similar—hey follow similar rules—but can be completely divergent… an infinite number of possibilities in the scenes that it generates.

This is kind of like chat. I’m talking to the system, but the reply is coming to the UI engine instead. So I’m giving the system an instruction, and the system is giving the interface an instruction for how to present that.

It’s actually pretty simple. The instructions are straightforward: update the CSS values for background and foreground color; update the text caption and font family; and then add a CSS animation and glow tuned to the mood of the scene. The machinery itself is pretty simple.

You are creative director

Josh

This brings us so to chapter four: how do we build this stuff? Chapter four of five, friends—you’re making excellent time. Let’s talk about how this works in practice and how your role changes when you create things like this.

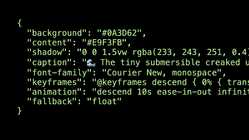

We’ll talk a little bit about how we developed this little Sentient Scenes exploration. We started by just asking in chat informal prompts like this to see what kinds of responses we’d get. So we’d ask OpenAI questions like this. And then, as we started to get a sense of how it would respond, we started to add a little bit more, asking it to respond in a more structured way starting with something simple like markdown format.

And we started to get responses like this. It’s telling me what colors it would suggest, the caption—and a really creepy blood emoji. Creepy! There’s some darkness to Open AI, friends!

As we kept refining the prompt, this is how the final prompt begins:

You are a scene generation assistant that creates animated stories. Your output defines a scene by controlling a character, a square div, that moves based on the user’s description. The character always starts at the center of the viewport. You will provide the colors, font, animation, and text description to match the story’s topic and mood. For movement, we gave it some high-level creative direction for how to apply animation to different moods for things like action scenes or peaceful scenes or suspenseful scenes, sleepy things.

So we’re telling it to identify what the mood of the description is, think about how that translates to motion. We did similar things with font choices.

And then we gave it some specific instructions for how to format the response. This is how the final response is always formatted when it comes back.

I’m chatting with the OpenAI chat API, but its response always comes back with using these colors for background and foreground. Here is the CSS to apply for the shadow or glow effect. Here’s the caption text, the font family, and so on. And it just inserts the things into there. Again, the machinery of this interface is pretty simple.

We taught it how to do things just by chatting with the interface and refining our prompt. Crafting these prompts was the central design activity. More than sketching UI, we sketched prompts, guidance to the system for how to behave.

More than sketching UI, we sketched prompts, guidance to the system for how to behave.

So as we create these open-ended AI mediated experiences, our work becomes more meta. We’re no longer doing each sort of specific interaction, but we’re defining the rules and the physics for this tiny little universe. We are becoming the creative directors for this. We define the parameters for the possibilities, and then we step back so that the system and the user can collaborate in this very tightly defined sandbox that we’ve created.

Prompt as requirements doc

Veronika

Right, so the prompt does triple duty, bridging all of the things. It provides technical direction, creative direction, product direction.

It used to be that programming app behavior was the exclusive realm of developers, and that’s not true anymore. Designers and product folks can come in and get their hands on the action. They can do this just by describing how they want the app to work.

The prompt becomes a hybrid artifact to run the whole show. So it’s part design documentation, part requirements doc, part programming language.

And it’s also technically very easy, just talking to a prompt.

Josh

I mean, how much time did it take us to make this?

Veronika

Like not even a day. It was so fast.

Josh

Yeah. It’s just plain-language requirements documentation and creative direction that we’re giving the system to understand and approach the problem.

So it’s not just a technical challenge. It’s more a challenge of imagination. And part of that imagination is how to talk to these systems in ways that go beyond simple conversation.

So here is an example of how to think about the different ways that we can ask these systems to communicate with us in order to speak UI.

I’m talking to ChatGPT here, and I’m going to start by asking it to respond to me only in French. These things are very fluid in their language. So it says, “bien sûr,” we’re gonna speak in French now.

It’s not a technical challenge. It’s a challenge of imagination.

I don’t know, let’s actually tell it to respond to me only in JSON. So it gives me a JSON object with a property “réponse” and value “bien sûr.” All right, so now let’s ask for some information. “What are the top three museums in Paris?” And it gives me a JSON object of “musée” items and with an array of all the museums and the descriptions there.

All right, well let’s just flex a little bit and see if it can do it in Spanish. It’s changed up, and now it’s giving me this result, the same response in Spanish, so I’m looking at “muséo” instead of “musée.”

Let’s see if it can speak UI. “I want to display this list as a carousel of cards on a website, so provide the properties to provide to this carousel object.” It’s still responding in JSON, so it’s structured data. Here’s a carousel object with an array of items, and each one has the same description that we were looking at before. It’s even included an image URL, and wait a second, it’s even suggesting some interaction rules to include in the carousel for autoplay.

I don’t know, let’s just ask for the interface at this point. So it’s gonna give me the HTML, and it’s generating it here. You can see it’s got some style sheets in there and some CSS styles embedded, and here’s the content that we were seeing before. OpenAI is a little old-school, so we have some jQuery in here.

Let’s see if it gets the job done. I chucked it into the browser, and all that I touched was to replace those placeholder images with real images—and we’ve got this real carousel.

Again, though, the point is not that LLM can generate working code.

An amazing chameleon

Veronika

Right. The point here is that LLM is an amazing chameleon.

Content can be translated and transformed into whatever form or tone or context you need in that moment. LLMs have internalized symbols—of language, of visuals, of code—and they can summarize, remix, and translate that content for you.

Sometimes they can even turn those remixes into answers, but really they’re manipulating symbols for concepts and associations between those symbols. They can summarize concepts, but they don’t seem to have any real understanding of them.

So how do we navigate these relative strengths and weaknesses?

That brings us to chapter 5, the new face of your interface. If generative AI can be so nimble in manner and format, we can think about generative AI in a new way. That is the face of your interface.

LLM as bullshitter and con artist

Speaking of faces, hello. Did you all see this movie Catch Me If You Can? Leonardo DiCaprio plays a con man, a master impersonator and criminal. He can get into any role or situation he wants. He’s a doctor. He’s an airline pilot. I think he’s a lawyer as well. He has the manner and he has this way about him, but he doesn’t actually have any knowledge.

Leo

What?

Airline agent

Are you my deadhead to Miami?

Leo

Yes, yes. Yeah, I’m your deadhead.

Airline agent

You’re a little late, but the jump seat is open.

Leo

It’s been a while since I’ve done this. Which one’s the jump seat again?

Veronika

So he’s able to do all this talking and now he can really communicate in a way that has convinced this airline worker that he should be able to get on a plane for free.

Pilot

You turning around on the red eye?

Leo

I’m jumping puddles for the next few months trying to earn my keep running leapfrogs for the weak and weary.

Veronika

Look at him go! He has absolutely no idea what he’s talking about, but he knows how to carry it. So he’s convincing everyone around him. He has that command of jargon, context, and tone. But he still doesn’t know how to fly the plane.

This is what LLMs do. They talk the talk, but they don’t understand the meaning. They don’t know what they’re talking about. They don’t have any real-world knowledge.

When you say something like “give me the answer,” what it hears is: “give me something that looks like the answer.” That’s what it’s really doing. It’s just putting together words in a way that seems statistically most likely.

When you say, “give me the answer,” the LLM hears: “give me something that looks like the answer.”

The miracle here—and it’s amazing and feels magical—is that this often actually gives you a genuinely correct answer. But if LLMs are only right 90% of the time, what about the other 10%? What are we supposed to do with that?

Worse, when they’re really convincing and confident, how do we know when they’re right and when they’re not? This is especially a problem when you’re working in a high-stakes situation like healthcare, airline safety, financial regulation, or even just, I don’t know… drawing a picture of ramen.

@teddywang86 ChatGPT, Show Me A Bowl Of Ramen

♬ original sound - TEDDY

User

ChatGPT, show me a bowl of ramen.

System

Here’s the illustration of a—

User

Get rid of the chopsticks.

System

Here’s the revised—

User

ChatGPT, show me a bowl of ramen.

User

Now there’s three chopsticks!

System

I apologize for the—

User

Now there’s four!

System

Let’s generate the—

User

I still see them.

System

Here’s the revised—

User

Do you see those two long brown things?

System

I’m unable to visually—

User

Show me what a pair of chopsticks looks like.

System

Here is the illustration of a—

User

I don’t want to see these two things with my bowl of ramen!

System

Here’s the new—

User

What are those two stick-looking things on the right side of the—

System

I can’t visually inspect the images.

User

What do you mean you can’t see the picture? You drew it!

Veronika

So it’s a lot of yelling, but I think we’ve all shared that frustration.

It literally cannot conceive of ramen without chopsticks, but it actually doesn’t even know what ramen is or what chopsticks are. It doesn’t have any relationship to them. It has a mathematical concept of ramen that is so close to the mathematical concept of chopsticks that it can’t even separate the two of them.

Present results as signals, not facts

Veronika

AI and machine learning don’t deal in facts. They deal in probabilities. There’s no black and white. It’s only about scales of gray. And what this means is that they’re delivering signals, not hard truth. We need to adapt that understanding in order to make our presentation of these more effective.

Josh

Large language models are not answer machines. They are dream machines.

This is a feature, not a bug. This is how they were designed—to imagine what could happen next from any premise, any seed text in the case of large language models.

Large language models are not answer machines. They are dream machines.

As designers, though, we often present these signals as facts. We don’t show the nuance or texture of these things being signals instead of facts. One of the things that we can do is start to think about how do we start to caveat the presentation to match the fact that these are probabilities, not absolutes.

Maybe these things are going to get better at answers. Maybe they will hallucinate less. Also, maybe not.

A really interesting line of design inquiry is: how can we make their weirdness an asset instead of a liability? We’ve been putting a lot of effort into fighting their essential nature—the way that they’re built, the fact that they aren’t good at facts and answers. How can we start to embrace that nature instead of fight it?

And in the meantime, what do we do?

Veronika

Let’s not let the LLMs fly the plane, how about that?

Machine intelligence for presentation, not facts

Veronika

Here’s what we suggest. We suggest using the LLM as the face of your system. They’re remarkably good interfaces. They can understand and express language in many forms. They’re a very friendly host that can welcome you and understand your intent and reply in a way that feels natural.

But for specific, especially technical data, they need to talk to other smarter, more grounded systems to get the actual facts. But in the meantime, they can present content in really varied ways.

Let’s not let the LLMs fly the plane, how about that?

Josh

That is really what we’re talking about when we talk about AI-mediated experiences. Large language models can understand intent and presentation, and they let us be nimble and expansive in the kinds of presentations that we can create.

What happens now if we’ve got systems that can actually translate experiences into different forms and interaction models? That might give us things that we’ve always wanted to do, but we don’t have the time and resources to do it.

They can transform that content from something static into something a lot more interesting.

Veronika

Should we talk about PDFs? There’s so much content trapped in PDFs. Very static—no interaction, frozen—almost like a content prison, to be a little bit dramatic. LLMs can really help here.

Machine intelligence can liberate this frozen content from its chains. I have a hunch many of you have used NotebookLM, which is Google AI’s powered research tool. We gave it a PDF of the Sentient Design book manuscript, and in a little under three minutes, it generated this 12-minute podcast-style conversation about our book.

AI speaker 1

Ready to dive into some really cool stuff? We’re gonna be talking about Sentient Design today.

AI speaker 2

Sentient Design, yeah. It’s pretty wild, right? Like instead of us trying to figure out how computers think, they’re starting to think more like us. Seriously, it’s like this whole new way of looking at how we use technology.

AI speaker 1

So we’ve got excerpts from a book called Sentient Design by Josh Clark and Veronika Kindred.

AI speaker 2

Yeah, good book.

Josh

“Good book, “Veronika! You heard it here first, everyone. Anyway, we’ve got a book. We’ve got some postcards up here, too. Thank you.

Well, that’s bonkers, right? I mean the script, the voices, all of it is AI. And now you’ve even got a thing where you can go in and ask it questions, ask those two podcast interviewers questions.

The quality is remarkable. The tone is just right for exactly this style of conversation, American-style podcasting.

But that’s not the most interesting thing about it. Veronika, you’ve always made some really good points about this, that it’s not about AI replacing human podcasts.

New formats, use cases, and audiences

Veronika

Right, by transforming the content from one form to another—by going from PDFs to podcasts—you’re enabling a whole new use case. There’s a whole new experience for the content, and it can be any content. So it’s like Josh said, the interesting thing is not that it might replace podcasts.

What’s really cool here is that it’s enabling a podcast for an audience of one. It’s a podcast that never would have existed unless you wanted it to exist. So instead of a hundred pages of PDF to wade through—which requires your eyes, your time, your attention—you’ve got a very casual, relatable conversation that you can listen to on the go, in your car, whenever you don’t have hands free. It’s just for you in a specific moment when you need it.

What becomes possible when you liberate this content? What happens when it becomes really easy to do that?

This is one of the superpowers of generative AI—not the generation specifically, but how it can understand meaning in one context and change it quickly to another, whether that’s another language, another medium, another data format. It understands concepts and can transform them into different shapes.

It’s a really cool question to think about: what does this transformation enable for the interfaces that you create and the content and data that you work with?

One thing that we urge you all to do is to focus on the experience, not the artifact, and that’s really the exciting bit that generative AI enables for interaction designers.

It’s less about the output and more about the outcome: what is the user trying to do and how do we enable that in the most graceful way possible? What kinds of new experiences does the machine intelligence let us enable?

Collaboration with a NPC

Josh

For example, what does explicit collaboration look like with AI?

Figma and its generation of software introduced the multiplayer experience—collaboration tools where we’re all working within the same environment to make comments, to contribute work, to ask questions.

Now we can add Sentient Design assistants to the mix, too. So suddenly we have multiplayer mode where we’re interacting not just with human colleagues, but AI assistants and agents.

We call this experience pattern the NPC pattern. NPC is a gaming term: non-player characters. It’s a player that’s run by the system instead of a person on the other side of the screen.

We’re familiar with some of this stuff already. This is what Slack bots are doing in your Slack channel. We understand that they’re not human, but they are behaving through the same channel as humans do, so we’re interacting with them in context as other users of the system.

Miro has a feature called sidekicks. They do things like give feedback on your content or suggest new content. We could be doing this just in a chat box, and ask it in chat to give me feedback on these things or create new suggestions. But instead Miro does it with an experience where the system acts as a user.

Here the NPC is called “product leader” and it behaves how a user would behave. How does it provide feedback? It goes through and it just adds comments. How does it add new content? It adds new sticky notes.

Here’s another example, a Chrome extension called Pointer that works in Google Docs. I’ve asked it to review my document for technical accuracy, and then it goes in and it makes suggestions just like a human editor would. I don’t have to go to some separate chat interface. It behaves as an NPC, a non-player character within the rules of the application.

Here you see the edits that it made. It does this as my account—I think that’s a limitation of the Chrome extension and how it has to work with Google Docs. It would get extra points, if it was clear that this was a bot doing this stuff instead—but as an experience pattern, it’s really solid.

Friends, intelligent interfaces are so much more than chat boxes and text fields. Under the hood, conversation with the system is what enables these experiences—but we don’t have to make it literal dialogue to make this stuff go.

Typing prompts is not the UX of the future. We don’t have to dial the clock back decades to command line interaction.

It’s experientially different and better to bring it directly into the interface context where you work. And that’s what we mean by weaving intelligence into the interface, into the experience, instead of bolting it on or forcing a switch to a different mode.

Typing prompts is not the UX of the future.

What we want to really encourage you all to do here is be really expansive in exploring the different shapes of intelligent interaction. We’ve seen a few new ones today. We’ve also seen what happens when you sprinkle a little intelligence onto existing interfaces to make proactive choices for the user.

But there are more. What are all the different possibilities that are emerging? Well, friends, get ready for… The Sentient Triangle!

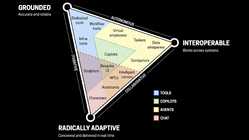

The Sentient Triangle

Josh

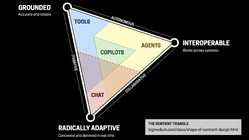

This builds upon some great work from Matt Webb of Interconnected.org, a terrific thinker about this stuff. It’s a triangle that charts different types of machine-intelligent experiences across three different criteria.

One is how grounded is the experience? Traditional computing experiences, for example, are grounded in fact and rules, really reliable. The same input gives you the same output.

Interoperable works across systems or across languages or across formats. So data scrapers live here, but also things that can talk to other systems like agents. We’ll talk about that in a second.

And then at the bottom, radically adaptive, which is really the new thing. Grounded and interoperable have been part of computing for forever. The radically adaptive part is what happens when you start to add some intelligence.

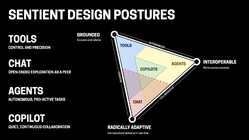

What you get when you combine these things are these four different postures. What we mean by postures is the way that these intelligent systems can relate to the user.

With tools, you have very traditional transactional computing interfaces. Here’s an input, here’s an output‚ very controlled, very explicit.

With chat, this tends to be a turn-based interaction with a peer. It’s not necessarily dialogue. Like what we saw with Sentient Scenes, it can be something where I’m talking to it and it’s responding—again, not necessarily in dialogue, but another turn-based peer behavior.

Agents… If tools and chat are behaviors that I need to manage, I delegate to agents. This is the thing where they decide what to do, go off and do it, decide when they’re done, and come back. I don’t have to supervise it when all goes well. It just comes back to me with the response.

And finally, copilots, which stake out the center and have elements of all of these things at once. They tend to be continuous and present, available to be asked questions like a chat experience, or to do actions for you like a tool, or to go off and do things for you like agents. It’s a combination of all of them, where their defining characteristic is that they are continuous and ambient.

When you zoom into a lower altitude, we’ve got 14 different experience patterns that we’ve identified so far. This list is not complete. It’s also impossible to show the full depth of these experiences on a two-dimensional chart. But this is a really good thinking tool to explore what kind of experiences emerge when you adjust the three characteristics.

We’ve talked about a few of these already—bespoke UI, NPCs, intelligent canvas. If you’re interested in finding out more of these, you don’t have to wait for the book. You can also just type into Google “the shape of Sentient Design,” and an article will come up giving you an overview of the Sentient Triangle. (This is a great use for a text box!)

This isn’t about AI

Veronika

When you walk away from this talk today, we hope you’ll get the point that we’ve really just been trying to pound home: This isn’t about AI, not really. It’s not “how do we use AI,” or “the market needs to have some more AI products or features.”

AI and machine learning are only software, and they’re a new material to us. They’re enablers.

Friends, this is really just software. It’s not magic. It’s a new technology to add to your toolkit. You learn the grain of this new material.

This is just software, not magic. Pull back from the magical thinking, and ask: What are these tools good at? What are they bad at?

Pull back from the magical thinking, and ask yourself: what are these tools good at? What are they bad at? What new problems can we solve? What friction can we help users overcome through contextual awareness and radical adaptivity? And perhaps the most important, can we justify the cost of using these tools?

Josh

The job of UX, after all, is to find these problems worth solving, right?

Veronika

That’s correct. We started this talk by asking Snoop what to do with AI.

Snoop Dogg

Like, do y’all know? Sh*t, what the f**k?

Veronika

And I think the point here is that you guys do know! You’ve got the knowledge and the skills and the experience to be able to use all these tools. It’s just that now you have a new design material to do them with.

You are needed more than ever

Josh

At its base, this is still fundamental UX practice. What is the problem to solve? What are the tools available to meet those problems and solve them in valuable ways?

We’re doing a lot of this work at Big Medium right now. Veronika and I are writing the book about it. (I don’t know if we mentioned that?) We’re helping companies understand how to put machine intelligence to meaningful use. We’re thinking about it strategically, doing some great product design as well. We’re doing workshops about Sentient Design and we’re doing Sentient Design sprints with our clients. We’re doing a full press on exploring what the possibilities are for this.

It is an exciting and weird time. We’re all in on this, but still realizing how much there is to learn and explore.

Here’s one thing that I do know: if we, the people in this room, if we don’t decide what this technology is for, it will decide for us. It’s up to us, not the technology, to figure out the right way to use it—and to do that with thought and with intention so that the technology doesn’t decide for us.

The future should not be self-driving.

The future should not be self-driving. And friends, that means you are needed more than ever. If any of you have steered clear of AI, if you’ve been skeptical of it—maybe fearful of it, uncertain—that makes so much sense. But it’s also all the more reason for you to engage with it.

The technology is being shaped right now, and so is its application. This is the moment to insert your values into this and help to steer this in the right direction as the industry finds its footing.

What values will you bring to this project? Bring your best selves to this next chapter. We have this astonishing new design material that can really elevate our craft and add really powerful new value to our products for our customers and for, in our case, our clients.

You have the tools available right now in your practice today to make something amazing. So we want to invite you to please go do that, friends. Go make something amazing.

Thanks very much.

Veronika

Thank you so much. Thank you everyone for coming. We’d love to add you to our professional network.

If you’re trying to understand the role of AI and machine intelligence in your products, we can help. Our Sentient Design practice includes product strategy, product design, workshops, and Sentient Design sprints. Get in touch to learn more.