The New Yorker this week reviews a book called “The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History since 1900” by David Edgerton, which challenges the notion of technology as one of novelty and invention. Lots of fascinating perspective there.

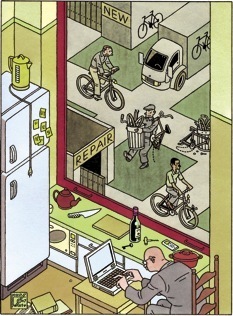

One interesting thread of the argument explores how innovations don’t always follow the path intended by the innovator. Ideas and inventions take on a life of their own once they’re released into the wild.

The user community, in other words, owns and defines a technology as much or more than its creator. Reviewer Steven Shapin explains beautifully:

In 1817, Thomas Broadwood, a vastly successful English piano manufacturer, visited Beethoven in Vienna and, shortly after, sent the composer a top-of-the-line instrument. Which of these two men understood the piano better—the craftsman-entrepreneur whose product adorned drawing rooms throughout Europe or the deaf genius whose works are a glory of piano repertoire? Or, for that matter, Liszt, who later owned the piano, and could do things at the keyboard that no performer previously could, or the curator in the museum where it resides today? The piano is one thing to a pianist, another to a piano tuner, another to an interior designer with no interest in music, and yet another to a child who wants to avoid practicing. Ultimately, the narrative of what kind of thing a piano is must be a story of all these users.

Creating a technology is naturally an act of collaboration (sometimes of compromise) between maker and user. I might be the guy who actually writes the code, but it’s the way that the software is actually used that defines the product.