Your faithful correspondent fell under the browbeating eye of authority on a few recent and essentially trivial occasions, making me think a bit about the effects of control, rule enforcement and tone in my own work.

Twice in the last six months, I’ve been pulled over on the streets of Paris while riding my bike. Yes, friends, my bike. In one case, I was caught easing through a red light at an empty intersection. In another, I was riding the wrong way down a quiet one-way street. I was in the wrong in both cases, to be sure, but the response seemed oddly out of scale. Both times I was surrounded by four glowering cops, the object of lectures and even mild ridicule (“What, they don’t have stoplights in America?”).[ 1 ]

The police in Paris do love a traffic violation, and not just on the roads. I was running along the Seine this weekend and saw the river police pulling over a pleasure boat that was ambling its way down the river.

It’s not that these things shouldn’t be policed. What’s off-putting is the aggressive manner in which they’re pursued, the personally intimidating level of officialdom applied to mild offenses.

You find this blanket application of law and order inflexibly applied in lots of contexts here. A cashier gave me the wrong change at my neighborhood supermarket recently. After I pointed out that she still owed me three euros, she called a manager who arrived a couple of minutes later with a digital scale. The manager proceeded to weigh – to physically weigh! – every bill and coin in the register.

While she did this, the cashier shrugged and explained to me that anytime they have to take money out of the register, they have to weigh every last centime in the drawer. “They used to make us count it all, so this is actually a big improvement,” she said. “Much faster.”

The process took about ten minutes, all for three euros (a little under five bucks), a sum just barely enough for me to hang around, but small enough to make me marvel at the complexity of the exercise. The reason for the procedure is theft prevention, but is the potential theft of three euros worth closing a checkout lane for ten minutes?

There’s a word for it

The French word for police stops and security checks is contrôle. When you’re stopped, you’ve been contrôlée, or “controlled.”

It’s the perfect description. You do feel controlled, subjected to an arbitrary display of authority that is often oversized for the offense. It’s frustrating, irritating, occasionally humiliating. And you do frequently wonder if perhaps that’s the goal.

We all feel the same way from time to time about the software or websites we use:

- “Do they want to make it impossible for me to buy on their site?”

- “Are they trying to make me feel stupid?”

- “Is it their goal to frustrate me?”

Software, of course, is nothing more than an elaborate set of rules. The developer and the designer establish what you can and cannot do and, even more crucially, set the tone and manner in which those rules are enforced. With proper care and presentation, users can be gently guided through the rules and limitations of the software. If done poorly, the rules simply seem arbitrary, even punitive.

Online, web forms are the chief instrument for bludgeoning users. Some of my favorites:

- Inflexible format rules (e.g., no spaces allowed in credit card numbers, phone fields that won’t accept international numbers)

- Required fields that aren’t really necessary

- Wiping out the contents of an entire form if you make a single mistake

- Notifications of problems with your submission only after you’ve filled out the entire form

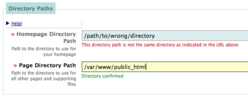

In the Big Medium CMS, I’ve tried to make tone and control as supportive as possible, to help editors understand the rules and work through them when they stumble. If there’s a problem with a field, a notice appears immediately to let you know, often with suggestions on how to fix it.

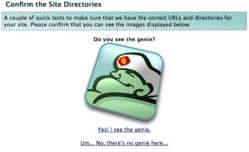

My personal favorite in this category is Big Medium’s setup wizard, which asks for locations of various directories on the server. As you go through each one, Big Medium checks the location on the fly to let you know if you got it right. The dropdown help window offers tips to help you find your way. After you choose the directories, a simple “can you see this image” test helps you verify that all is well. A potentially frustrating experience is made friendly. Control without being controlling.

Our fault, not yours

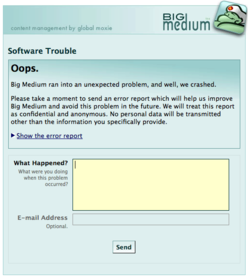

Tone is especially important when something goes wrong with your application or website. There should be some explanation, along with implied humility: “It’s the software’s fault, not yours, let us help make this right.”

In the rare instances that Big Medium crashes, for example, editors see an “oops” message along with an invitation to send a crash report to me. These messages automatically open a support ticket on the Big Medium server. If a Big Medium installation crashes anywhere in the world, I know about it. If the editor chooses to provide an e-mail address, I’m able to provide help immediately.

Instead of conveying a shrug or, worse, a pointing finger, the error message is turned into an opportunity to get help.

The same principle is at work in this classic article from “A List Apart”: The Perfect 404. Ian Lloyd details how a “file not found” page can be transformed into a resource to help the lost visitor find what they’re looking for. “Don’t get off on the wrong foot with this visitor to your site,” he writes. “You might yet turn this problem around.”

Hey, it’s a lot better than sending four Paris cops to mock them.

1. Side rant: Bicyclists are pulled over all the time here for minor traffic violations, but I’ve never once seen anyone stopped for riding a motorcycle on the sidewalk, which happens all the time. Makes me crazy. [back]