“This conference can’t be about doing business as usual when terrible things are happening in the world. It’s got to be about what we can do to make the world better.”

That’s what I told over 1100 interaction designers when John Payne and I opened the Interaction 17 conference last month. As co-chairs, John and I had considered and shaped the event’s program for over a year with our steering committee. We decided early on that Interaction 17 would consider how to design for the fast-moving contexts of our culture, industry, and craft. Over three days, the main conference addressed what to make of emerging interfaces and new design process. But more crucially, the event examined the responsibilities of designers in wielding those technologies.

I couldn’t be more pleased with how it turned out. Designers leaned into these sessions with a sense of mission. Two weeks into the Trump presidency, as our international audience negotiated the president’s travel ban at our border, the conference hall was thick with questions about what makes a good society—and what designers’ role in it should be.

With the design community all in one place, it's clear that the natives are restless. #ixd17

— Rachel Ilan (@rilan) February 6, 2017

I’m quite impressed with the political overtones at this year’s Interactions conference. Designers need to be politically active. #ixd17

— Thomas Wendt (@Thomas_Wendt) February 7, 2017

We talked about how to design in the era of the algorithm, of data surveillance, of bad data (and misinformation). We talked about how our services can earn trust and foster respect as our interfaces become more intimate, more knowing, more ubiquitous, leaping off our screens and into our homes or onto our bodies. We asked how new technologies like virtual reality, chatbots, and the internet of things can be used in meaningful ways that go beyond novelty and address real purpose.

We focused not only on how to do design, but _why_—to what end and to whose benefit.

Throughout, the constant subtext was to look beyond our interfaces and at their impact. What are the intended and unintended consequences of our work at both societal and individual levels? As digital interfaces mediate more and more of our personal, social, and civic lives, how can designers shape behavior to amplify our humanity, build human connection, and empower the disempowered?

“The people here design, make, and control the experiences had by millions of humans,” said Chelsea Mauldin, executive director of Public Policy Lab, in her opening keynote Design and Power. “We alter the life experiences, the social relationships, the fabric of the lives of millions of people. … How do we use that power to alter our users’ lives in ways that are meaningful for them?”

“We should be building the technology for the world we all want to live in,” said Third Wave Fashion’s Liza Kindred, the smartest person I know. Her talk Mindful Technology offered antidotes to our industry’s dubious focus on constant engagement. “The same way we can take a deep breath before we reach for our phones, we can also take a moment during our design process: step back and just think about our values—and whether we’re actually designing something we want to put out there.” (Liza’s launching a new venture, Mindful Technology, to help companies and individuals align their tech with core values.)

Indeed, nearly every session reminded that design is much more than technique. Designers have to be more explicitly thoughtful about the principles that define our work.

Several strong themes emerged across the three days:

- Software is ideology

- Information is subtle, subject to bias and error

- Design + humility = respect

- Efficiency isn’t the be-all and end-all

- Talk to objects, talk to services

- New tech creates new behaviors

- We still don’t really know what we’re doing

- Safe places foster creative risk

- We are the leaders we’ve been waiting for

That’s the TL;DR. Below is a bunch of rumination on the details, albeit on just a sliver of the talks. The good news: all talks were recorded, and the videos have begun to make it online at the IxDA Vimeo account, with more on the way.

1. Software is ideology

The work of interaction design is to shape behavior. The way designers choose to do that is full of value decisions, whether conscious or not. When you stack those decisions up, you get software that is opinionated, even ideological, and which shapes the culture of its use.

- Do we give users agency (help cook a healthy meal) or replace it (food delivery)?

- Do we reveal how decisions are made, or is the algorithm a magical black box?

- Is the goal efficiency, or to add texture to an experience?

- Are we designing for accessibility or a privileged few?

- Do we want to trap users in our service or give them freedom?

“We are in an industry where we are pushed to create new products fast without necessarily thinking how that impacts our life, our values, our culture,” said Simone Rebaudengo in his talk, Domesticating Intelligence. “We really need to think deeply about what motives are behind the objects that we create, and what types of relationships we want to create.”

Simone and others encouraged designers to explicitly consider their own values as well as the implicit values of the products they make. It’s worthwhile. In my own practice, I constantly revisit a list of design principles that I believe are important for technology today. And at the start of every client project, I work with stakeholders to set out the design principles that will govern the project.

“Design is applied ethics,” said Cennydd Bowles in his talk Ethics for the AI Age. Cennydd offered four ethical tests as a way to check the values of what you’re doing:

- What if everyone did what I’m about to do?

- Am I treating people as ends or means?

- Am I maximizing happiness for the greatest number?

- Would I be happy for this to be published in tomorrow’s papers?

Not for nothing, but it’s pretty clear that companies like Uber—especially Uber—routinely fail all those tests. So what instead? Consider this set of design principles Liza proposed in her Mindful Technology talk:

- Design for human connection.

- Awake the senses.

- Create utility or joy.

- Let the tech disappear.

- Design for disconnect.

- Build extensibly.

- Simplify. Then simplify again.

- Narrow the digital divide.

- Make something the world needs.

2. Information is subtle, subject to bias and error

Fact and truth have become slippery: the partial perspectives of our social-media bubbles, the outright lies of our leaders, bad assumptions that throw off our algorithms, tainted data in our applications. The presentation of information has become not only challenging but controversial.

As designers, that first means we have to accept that our worldviews—even when objectively true—are not shared by all. “GOOB: get out of your bubble,” said Chelsey Delaney, director of digital UX for Planned Parenthood, in her talk Designing To Combat Misinformation. “The more we are grounded in our own biases, the more we are polarized by our own biases.”

Chelsea shared how her organization tackles damaging but closely held healthcare myths (what you can and cannot catch from toilet seats, for example). She counseled compassion, suggesting that designers seek out the source of misinformation and get to know the communities where it springs from: research for the win. From there, plainspoken presentation of myth vs fact, with clear paths to alternate, detailed explanations prove effective.

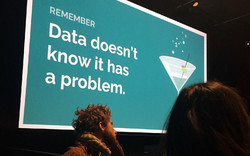

But what about when that bad information springs from our own data? As more and more of us build services upon sprawling heaps of data, several talks suggested that we have to treat our own data with skepticism—and sometimes as hostile.

“Data is a lot like a drunk aunt,” said Sonia Koesterer of Collective Health in her talk, Not Dead Yet: Designing Great Experiences with Bad Data. “She’ll go on and on talking, she’ll blurt out numbers everywhere, but she’s never going to tell you that she’s had too much to drink. She’s never going to tell you hey, you maybe should stop taking me seriously right about now and it’s really up to all of us to understand that she’s off her game.”

Sonia suggested a slow-burn prototyping process to make sure you live with your data long enough to understand whether you’re building the right thing in a reliable way. Build forcing functions that bail out at the first whiff of bad data. Establish redundant data checks to confirm your data is actually what it says it is—almost like how you secure your services by making sure users are who they say they are.

This kind of “garbage in, garbage out” sensibility seems like common sense, yet our culture tends to embrace a “garbage in, gospel out” ethic instead. We have unreasonable trust in the output of the algorithm—just because it’s an algorithm.

What if Alexa is the drunk aunt? And how do we correct Alexa when the algorithm is off-kilter?

“We think that objects [and algorithms] are objective, that they are better than humans at making decisions because they don’t have emotions or they don’t have biases,” said Simone Rebaudengo. “Computers themselves have biases that are baked in the data that we feed them.”

Trouble is, we often don’t understand those biases because the decision-making process is invisible to us.

“Why should I trust Alexa?” asked Simone. “What is the logic behind it? And if I don’t have any clue, what can I do about it? Right now these things are very black box, but at a certain point it will have to be more transparent.”

3.Design + humility = respect

“Good design takes a certain amount of humility,” Dori Tunstall reminded us in her keynote, Respectful Design.

At the moment, too many of our products lack humility; they are noisy, clamoring for more attention than the underlying service actually deserves in the larger context of our lives. We have to do better at scaling the attention our applications demand to the importance they properly have in people’s lives.

That was the strong thesis of Liza Kindred’s talk, questioning our industry’s drive to engagement, and our love affair with our own products. “People don’t really care about technology,” Liza said. “When it comes down to it we really care about ourselves and our loved ones more than the gadgets and the interfaces. We want to connect with the people we love. … Allow people to stay in their moment. … Have the judgment not to interrupt when it’s not necessarily important.”

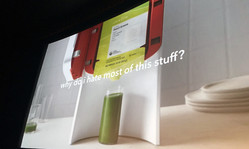

Ours is an industry that tends to assume technology will always make things better. It’s all too rare to ask ourselves if specific contexts would perhaps be easier without that nifty new tech. The light switch, after all, remains the gold standard of interaction design, despite attempts to “improve” on it with fancier technology. “I have never had a harder time turning my lights on since we hooked them up to Alexa,” Liza said. “That is an example for me of the technology getting in the way.”

Questioning the current tech onslaught does not make you a Luddite. It makes you smart and aware. #ixd17

— Gary Schroeder (@gary_schroeder) February 8, 2017

“The opportunity space here is: what do we not design?” said Matt Yurdana of Intel’s IoT Experiences Group in a talk about establishing trust with self-driving cars. “Where are those places in this new space and in other newly connected spaces where we want the technology to be out of the way, and not necessarily mediate social interactions between people in all contexts?”

This question popped up in lots of ways at Interaction as designers wrestled with the appropriate moments to cede agency—and sometimes control—to the robots.

4. Efficiency isn’t the be-all and end-all

“There are a series of products that see life as a problem,” Simone said. “You know, where your kitchen is a big gigantic problem to solve, and where efficiency is the main value.”

A core value of Silicon Valley is the relentless elimination of friction and the creation of highly efficient services that reduce effort and even predict our wants and needs. Often the “friction” that’s eliminated is a conversation with another human being. In other words, sometimes the friction we’re removing is actually the texture of life.

“Look, I like a nice efficient interface as much as anyone else,” said Brendan Dawes in his keynote The Beautiful Inconvenience of Things. You want that thing to get out of the way. But sometimes what I would like to explore is interfaces for encouraging serendipity … in such a way that you can bump into things.”

“We imagine it’s all going to be automated,” said Pamela Pavilscak in her talk When Your Internet Things Know How You Feel. “It’s rational, frictionless, invisible. … The problem is that our experience of technology is not really rational. We have an emotional attachment to our objects. We touch our phones hundreds of times a day, probably, sadly, more than we touch our partners or our children or our pets. … What if our objects had a little more compassion and empathy and etiquette about us?”

5. Talk to objects, talk to services

If efficiency isn’t always the goal, then there’s an exciting opportunity to introduce wonderfully human inefficiencies in the way we talk to data services. It means that push-button interactions may sometimes be replaced by conversation or physical interaction. Emotion and personality play a stronger role.

Brendan shared lots of his hardware projects, all of which blend physical and digital in ways that amplify the meaning of the object in our lives—making it more of what it already is. He shared a New York City snow globe that, when you shake it, tells his computer to show photos from a long-ago NYC visit: “Physical artifacts as digital interfaces. We have these artifacts in our home, and they’re there to maybe remind us of something. … So these objects, they tell us things, they talk to us.”

More and more data services are explicitly talking these days, through speech interfaces like Alexa or Siri, or through a wave of chatbots in our messaging interfaces. I hosted an afternoon of sessions about conversational interface design. Paul Pangaro, Whitney French, Elizabeth Allen, Greg Vassallo and Elena Ontiveros tackled various angles of designing, prototyping, and managing bots—and considering what’s a conversation in the first place.

Much of the talk about these conversations with systems revolved around issues of tone, how to avoid the uncanny valley of robots that try too hard (and unsuccessfully) to be human. “I would like to see technology that is more humane, not necessarily more human,” Pamela Pavliscak said in a separate session. The work here is to establish appropriate expectations for the conversations people can have with bots—and to create systems that are smart enough to know when they’re not smart enough.

As it turns out, the very “botness” of these interactions tends to spur some new and productive behaviors: people are often much more open, even vulnerable, when talking to bots versus talking to humans.

Yet some things remain the same: we care what the “person” we talk to thinks of us—even when they’re robots. We change our behavior because we know they’re watching/listening. “We are becoming aware of the fact that there are a lot of algorithms that are learning about our life, and a lot of people are starting to define their own strategies to train objects and train algorithms,” said Simone Rebaudengo. He mentioned Spotify’s Discover Weekly playlists, which gather new music based on your listening history. “The first time I started using it, it only played German techno. And I kind of felt shit about myself, so I started listening to other music to mix up my feed and feel better about myself.”

6. New tech creates new behaviors

In her talk VR and AR: What’s the Story, Brenda Laurel kicked off a spirited discussion of virtual reality. “You should be able to support emergent goals and behaviors,” she said. “The more stuff that’s in there that’s reactive, interactive, responsive, the better.”

Part of our jobs as designers of new interfaces is to provide people with enough freedom that they can pursue unanticipated but productive new uses of those systems. Our virtual realities, in other words, are creating new realities in “reality prime” as Brenda called it.

“I have dreams in VR now, because I’ve been using it so much,” said filmmaker Gary Hustwit in his talk Unframed about VR filmmaking. “I also have dreams about new VR experiences that don’t exist yet, which is even weirder.”

These were potent reminders that new categories of tech products tend to have strong ripple effects beyond the product itself. Matt Yurdana struck a similar theme when he quoted poet Stephen Dunn: “Normal: the most malleable word our century has known. The light bulb changed the evening. The car invented the motel.” Matt said:

Right now the focus [for self-driving cars] is on the vehicle, getting it to drive automatically, but in the long run, it’s not really about the vehicle, it’s about what is our changing notion of getting from Point A to Point B, how it’s going to transform the infrastructure in which we travel through. How will this work reshape and redesign our cities and our suburbs?

7. We still don’t really know what we’re doing

“I think I’ve distilled what this conference is all about,” Jeremy Keith quipped to me during one of the breaks. “It’s about how we’ll save the world through some nightmarish combination of virtual reality, chatbots, and self-driving cars.”

I’m not sure I’d put it exactly that way 😉, but Jeremy’s right to bring some skepticism to this. Heedlessly deployed, these new technologies could indeed stitch together a nightmare of bad experiences that hinder more than help, that distance us from the world and from each other. There are a million ways we could get this wrong, and we don’t yet know what these emerging interfaces are truly for—or what good or harm they might do.

This is all happening so quickly and for such a diversity of digital systems, we haven’t come close to establishing best practices for any of them. With so many unknown potential consequences—long-term consequences—of our work, it’s likely to be a while before those best practices fully bake.

"The world's most depressing venn diagram." -Nathan Moody #ixd17 pic.twitter.com/LGjGYVtBQN

— Small Planet (@SmallPlanetApps) February 7, 2017

So, more than ever, we need to experiment, research, and prototype. And in that research we need to try some zany and unexpected ideas. We need to accept that our expertise in the point-and-click medium may have only limited application in these emerging interfaces.

“When designing the future, you need to constantly question your known tricks,” said Artefact’s Brad Crane in Suspending Disbelief: Building Immersive Designs for the Future, his talk with Jon Mann.

“Put things into the world that deserve to exist,” said Brendan Dawes. “That thing in your notebook that you’ve never made doesn’t change anything. You’ve got to make these things real, even in a lo-fi way. You’ve got to put it out there.”

8. Safe places foster creative risk

If we’re going to go outside of our comfort zones to explore truly new and meaningful uses of new technologies, our organizations and processes need to be not only creative, but creatively safe. Trying new things inevitably means failing at new things, and that can be bruising.

“The role of design leadership is to focus on building trust as much as you focus on building craft,” said Jon Kolko in his talk Sh*t Sh*w: Creative Clarity in the Midst of Ambiguity. Design leaders, he said, can create an atmosphere of trust and collaboration by framing questions and demonstrating that possible solutions are only steps in the journey, not the end of it:

You begin the negotiation by making something and you acknowledge when you make it that it’s wrong. The whole point is to start the snowball effect. The whole point is not to be right. That takes an awful lot of pressure and burden off of you. You don’t have to be the biggest brain in the room. … The mindset of a creative director shouldn’t be, “I’m the person who has to have the good idea.” Instead, you’re the person who simply needs to be able to articulate the problem.

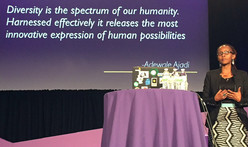

Many talks brought home the importance of diverse viewpoints in teasing out the most creative results—not only for sturdy products but for sturdy values.

“Diversity is an ethical early-warning system,” Cennydd Bowles said. “A homogenous group can really only focus on likely impacts for people like them. But a team with diverse traits and acquired experiences, they can better anticipate what’s going to go wrong further down a path. … Most unethical design and decisions happen because of insular thinking.”

Dori Tunstall’s keynote especially brought this home in the telling of her focused effort to bring more indigenous designers into the faculty of Ontario College of Art and Design: “Respectful design is really about designing futures of inclusion and belonging for everyone and everything.”

9. We are the leaders we’ve been waiting for

In a moment as divisive as this one, when the stakes are so high, it wasn’t a surprise that so many designers came to Interaction looking for ways they can personally make the world a better place. Speaker after speaker gave the audience permission to just go and do it.

“Part of our gift as designers is that we bring things into the world, and we can bring in new conversations into our organizations,” said Hannah Du Plessis in her thoughtful closing keynote with Marc Rettig.

All of us are empowered—even obliged—to go and figure out how to make the world better… how to make power more evenly distributed… how to make justice more universal.

“The great thing about design is that we make the work tangible,” said Dori Tunstall. “We can make justice tangible, too.”

Here’s the thing, though: design is commercial work. And that means it has to deliver business value in order to justify itself.

“We want to serve the people, but we have to answer to the man.”

—Chelsea Mauldin, Design and Power

“However much we want to embrace this user-centered perspective, in the end, the people commissioning our services, our clients, the people employing us and paying our salaries, they actually have more power over what we deliver than our users. They have signoff," said Chelsea Mauldin in her opening keynote.

“When you create a new app or tool or platform,” she asked, “are you fundamentally serving the best interests of your users or the owners or shareholders who are going to profit from that thing that you’ve made? … Can you put your users first? Can you really put their interests before your own? Before your clients’ and your employers’? Can you say my first duty is to the wellbeing of my users?”

The best case, of course, addresses the needs of both user and shareholder. The hard work of user experience is to uncover the elusive path that connects user goals and business goals… and then light it as brightly as possible so that the business is encouraged to stick to that path. But power and money don’t always respect the path, instead choosing cynical designs that take advantage of the audience and corrupt the product. (This is what advertising always threatens to do to media properties, for example.)

So what can we do when we can’t find that narrow path, or when the powers that be refuse to follow it? Resist. Take ownership of what your role will and will not be.

Chelsea put it better than I possibly could:

There’s daily and challenging work to do right inside of our design practices. We can observe the exercise of power and resist its injustices. We can reject simplistic notions of our users and seek to understand ourselves in them—and to dedicate ourselves to act as their tools.

We can resist the very strong current of authority. We can resist state power, and we can also resist commercial power. And we can explore ways to alter or expand our orders. We will be given orders. The question is, whether we have to obey them exactly.

We can bear witness. We can raise our hands and our voices when we see our teams or our employers or ourselves taking actions that undermine the humanity of others.

We can refuse to carry out work that troubles our conscience or runs contrary to our moral commitments. And we can choose always to seek out work that is dedicated to empowering others, and empowering in particular the people who are more vulnerable, more in need, or maybe just less lucky than ourselves.

Ready for Action

As one of the organizers of the event, I’m admittedly biased. But wow, I found Interaction to be a powerful rallying cry for our craft and our industry—and for me personally. It’s already changed the way I think about both the micro and macro decisions in my work, from the niceties of interface language to the big-picture project work I’ll pursue this year.

But also, some sad news: I’m incredibly upset to report that Interaction speaker Whitney French died just weeks after the conference. Her tragic and senseless death through domestic violence is a huge loss; this thoughtful and generous young designer was just starting to hit her stride. The world is poorer because she’s no longer with us.

For me, this life cut short is another reminder that we can’t wait—yet another reason that this is no time for business as usual. Please: get after your work on making this the world we all want to live in.