“Algorithms Aren’t Racist. Your Skin Is Just Too Dark.”

By

Josh Clark

Published Jun 2, 2017

Joy Buolamwini on on a tear lately. The founder of the Algorithmic Justice League has received well-deserved press from the likes of the BBC and Guardian for her campaign to uncover inadvertent bias in machine-learning algorithms.

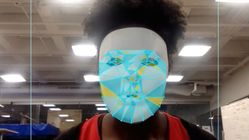

At Hackernoon, Buolamwini responds to criticism she received after demonstrating that facial recognition often breaks down for people of color. (Buolamwini, a woman of color, had to put on a white mask before one algorithm would even detect a face.) Some have told Buolamwini that it’s not the algorithm’s fault but rather that cameras are poor at discerning black faces: “Algorithms aren’t racist,” the argument goes. “Your skin is just too dark.”

Good lord. The problem is not with “photography.” If your eye can discern difference, the camera can, too. It’s true that camera technology has historically favored light skin. But that’s less a factor of underlying technology than of the skewed market forces and customer base that shaped early photography. In other words: it was a miserable design decision. For decades, for example, Kodak’s development process for color film was calibrated to photos called “Shirley cards” (named after the first model to pose for them). Shirley cards reflected a decidedly white concept of beauty. “In the early days, all of them were white and often tagged with the word ‘normal,’” NPR reported.

Now we’re carrying this original bias into the machine-learning era. Machine learning excels at determining what’s “normal” and trying to replicate it—or discard outliers. What the machines think is normal depends entirely on the data we feed their models. As the era of the algorithm begins to embrace the whole broad world, it’s urgent that we examine what “normal” really is and work to avoid propagating exclusionary notions of the past by encoding them into our models.

Instead of doing the hard work of creating truly inclusive algorithms, however, some suggest that Buolamwini should instead carry a lighting kit with her:

More than a few observers have recommended that instead of pointing out failures, I should simply make sure I use additional lighting. Silence is not the answer. The suggestion to get more lights to increase illumination in an already lit room is a stop gap solution. Suggesting people with dark skin keep extra lights around to better illuminate themselves misses the point.

Should we change ourselves to fit technology or make technology that fits us?

Who has to take extra steps to make technology work? Who are the default settings optimized for?

As always with emerging technologies, our challenge is making tech bend to our lives instead of the reverse. It’s profoundly unfair to make some lives bend more than others.

For designers, the arrival of the algorithm era introduces UX research challenges at an unprecedented scale. A big emerging job of design is to help identify where the prevailing definition of “normal” is flawed, and then move heaven and earth to make sure the data models embrace a new, more inclusive definition of normal. That is where we need to add more light.